Research impact: Refining crucial solar weather predictions for a NASA panel

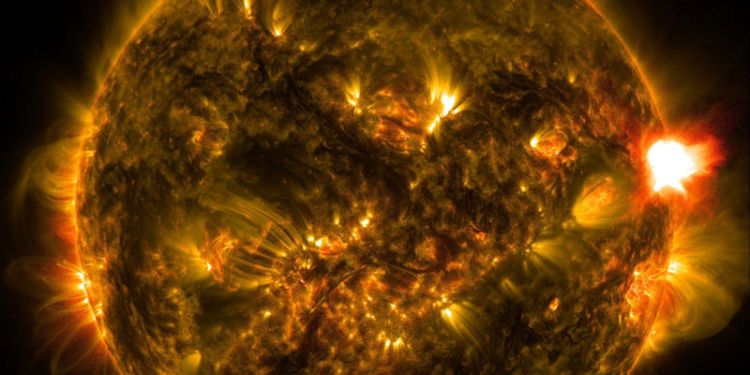

Space weather is strongly influenced by the sun’s activity, generated by the sun’s magnetic field. Solar flares, coronal mass ejections and sun spots are high-energy events that can directly affect radio and satellite communications, electricity grid operation and radiation levels on Earth; so predicting what the sun is going to do is of huge importance in operational and risk-planning.

The Solar Cycle Prediction Panel is an international group of experts co-sponsored by the US’s National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). It collates the most up to date research, theories and indicators to come up with the best available longer-term predictions for every successive solar cycle, each usually of ten or eleven years’ duration.

Professor Steven Tobias, Professor of Applied Mathematics at the University of Leeds, is an expert on dynamo theory: the science behind the generation of magnetic fields in the universe. In 2008 he was invited to present to the Solar Cycle 24 prediction panel in the United States as a consultant.

Professor Tobias says: “There were several competing dynamo theory prediction models that the panel was evaluating, some predicting very high activity but others low. I explained the limitations of these types of models generally in predicting solar activity.”

His information directly influenced the panel, leading to them reversing their initial view from a prediction of high solar activity in the next cycle, to a weak one. When Cycle 24 ended in 2019, that decision was proved to be accurate – it had indeed been a period of low solar activity. His work has modified the general standing of dynamo-based prediction schemes and changed the process for predicting long-term solar activity, with the next panel continuing to use his evidence when predicting activity for the current Cycle 25.

Knowing what the sun will be doing is essential for planners of satellite communications and electrical grid operators. For example, solar activity can affect how much energy is needed to launch a satellite, so launching at the optimum time can save millions of pounds. Likewise, if power operators know how likely a solar storm is to occur, they can plan for a risk of capacity blowouts.

In 2012, a coronal mass ejection barely missed Earth. A study by the US National Academy of Sciences concluded that a direct hit by such a ‘sun storm’ could cause some $2 trillion in economic damage to the US alone, shutting down the power grid and rendering satellites at least temporarily useless.

Scientists are now watching the present cycle closely, after the panel predicted that it would be one of low-activity, with sunspot activity peaking in 2025, but radically different competing predictions have been put forward elsewhere.

Professor Tobias concludes: “Predicting activity can be quite contentious. So the more accurate the panel can be every time with its research and science-based predictions, the better.”

Contact us

If you would like to discuss this area of research in more detail, please contact Professor Steven Tobias.