Research impact: Sanitation evidence prompts improved health measures for millions

Stark imagery – adorned with an even starker title – can capture the attention of policymakers and trigger new approaches to even the most basic challenges of life.

The Shit-Flow Diagram (SFD), supported by the Service Delivery Assessment (SDA), tools developed by a team at the University of Leeds and the World Bank, has transformed the disposal of the faecal waste of tens of millions of people in the global south.

More than 160 cities in middle and low income countries with a total population of 161 million have embraced the tools developed by Professor of Public Health Engineering Barbara Evans and her colleagues. The research has influenced investments in over 100 cities, such as Dar es Salaam and Dhaka, maximising public health benefits for over 1 million people.

The SFD visually represents the flows of ’safe’ and ‘unsafe’ faecal waste that result from a city’s sanitation system, while the SDA shows the underlying economic and practical drivers of a city’s sanitation performance, allowing policy and institutional gaps to be identified.

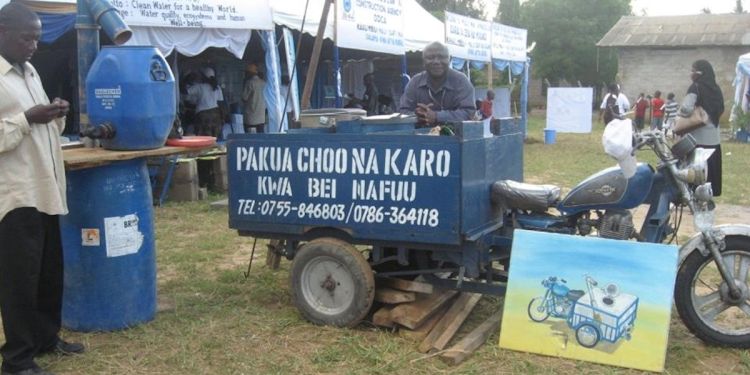

The tools are helping governments, cities and NGOs in low and middle-income countries overcome a bias towards the planning and engineering of sewerage systems which have typically only provided a sanitation solution for the old colonial city centres. This bias has been reinforced through development projects, and professional training, for the last 70 years.

Professor Evans, a leading member of the University’s ‘water@leeds’ research group, says: “Right from the start, the SFD graphic has had an impact on civic leaders; mayors are horrified. There is shock and dismay at the faecal waste lying around their cities. National governments have built SFDs into their sanitation planning programmes to encourage effective investment in on-site sanitation, such as pit latrines, that most people depend on.”

That shock impact can be vital, she suggests, as human waste is most certainly political.

“We could solve sanitation problems if we wanted to but the people affected are often hidden away. Giving people sanitation can be transformational.

“The SFD allows us to show governments that even if their ultimate goal is sewerage it will take 50 years, so they need alternatives – they need to look at what’s already in place and build on that.” The politics of excrement are changing. Improved sanitation was added at the last minute to the UN Millennial Development Goals in 2000 and, thanks in part to Professor Evans and her colleagues, was embedded in the UN Sustainable Development Goals in 2015.

The SFD allows us to show governments that even if their ultimate goal is sewerage it will take 50 years, so they need alternatives.

A strength of the SDA, Professor Evans says, is that it does not present one set solution. Instead, engineers, policymakers, communities and funders can use the tool to find answers that reflect local circumstances, funding and expertise.

This year the team launched an interactive website which allows users to intensively study the urban sanitation status of individual cities, countries and regions. A 2018 paper identified factors that ensured safer containment, emptying, discharge, delivery and treatment of faecal sludge. The paper proposed a range of intervention packages to effectively improve sanitation services.

Now Professor Evans and her colleagues, supported by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, are using the SFD to map pathogens, to explore the role that sanitation plays in climate change and how existing systems will cope with the impacts of increased flooding.

Contact us

If you would like to discuss this area of research in more detail, please contact Professor Barbara Evans.