Discovery of methanol in a 'warm' planet-forming disk

Astronomers have identified the molecule methanol in the ‘warm zones’ of a protoplanetary disk circling a star about 360 light years from Earth.

The finding is significant because although methanol - CH3OH - is one of the simpler complex carbon-based molecules, it is a precursor chemical involved in the creation of more complex substances such as amino acids and proteins, the building blocks of life.

The methanol was identified by an international team of astronomers, including scientists from the University of Leeds, studying a star known as HD 100546 and its protoplanetary disk, the swirling dust and gas from which a planet is born. They are about 10 million years old and located in the direction of the southern constellation of the Fly (Musca).

The study - An inherited complex organic molecule reservoir in a warm planet-hosting disk - has been published in the journal Nature Astronomy.

The astronomers say the methanol could not have formed in the warm zones of the disk, where temperatures are in excess of 20 Kelvin (-253 degrees Centigrade). Instead, they believe it was created as the protoplanetary disk formed when the dust and gas clouds were cooler.

Dr Alice Booth, who completed her PhD at the University of Leeds last year but is now at the University of Leiden, led the study. She said: "This is a very exciting and surprising result. This is the first clear observational evidence that complex organic molecules can be 'inherited' from the earlier cold dark clouds phase."

Dr Catherine Walsh and Dr John Ilee, both from the School of Physics and Astronomy at Leeds, were involved in the study.

The researchers used the ALMA radio observatory, located high up in the Chilean Andes. The observatory senses electromagnetic radiation emitted by molecules deep in space. The astronomers were looking for the molecule sulphur monoxide when, to their surprise, they detected evidence of methanol.

In the future, the researchers hope to search for more complex oxygen-containing molecules such as dimethyl ether (C2H6O), methyl formate (C2H4O2) and acetaldehyde (C2H4O). These molecules, which are also found in comets and dark clouds, are believed to some of the key ingredients for prebiotic chemistry.

The researchers want to compare the quantities of these substances in the planet-forming disk with the quantities in comets. This way, they can get a better idea of what proportion of the organic content survives the star formation process. And that, in turn, is important for a better understanding of the chemical processes during the formation of planets.

After all, icy asteroids such as comets are the building blocks of planets.

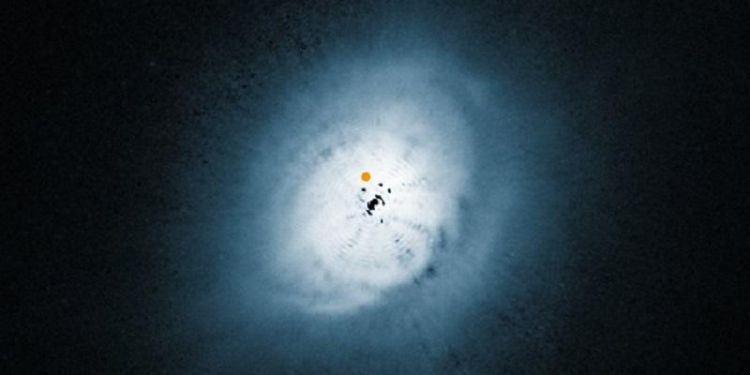

The top image from the Hubble space telescope shows the dust disk around the young star HD 100546. Picture courtesy of ESO/NASA/ESA/Ardila et al